Zener, our full-time shop cat, has discovered an unexpected application for the WaterColorBot. Not certain if we should add “cat bed” to its list of features.

Zener, our full-time shop cat, has discovered an unexpected application for the WaterColorBot. Not certain if we should add “cat bed” to its list of features.

Over on twitter, WaterColorBot co-conspirator Sylvia says,

Oh mah glob guys…I got some new winches for the watercolorbot!! Made of metal peeps!! :D #coraline #watercolorbot

An EggBot is a compact, easy to use art robot that can draw on small spherical and egg-shaped objects. The EggBot was originally invented by motion control artist Bruce Shapiro in 1990. Since then, EggBots have been used as educational and artistic pieces in museums and workshops. We have been working with Bruce since 2010 to design and manufacture EggBot kits, and our well-known Deluxe EggBot kit is a popular favorite at makerspaces and hackerspaces around the world.

Today we’re very proud to release the newest member of the family: the EggBot Pro, a near-complete reimagining of the EggBot, designed for rigidity, ease of use, and faster setup.

The EggBot Pro is as sturdy as can be: Its major components are all solid aluminum, CNC machined in the USA, and powder coated or anodized. (And isn’t it a beauty?)

The most common mechanical adjustments are faster with twin bicycle-style quick releases, and repositioned thumbscrews for easier access.

The frame also has an open front design that gives much better visibility while running, and greatly improved manual access when setting up.

And, it comes built, tested, and ready to use — no assembly required. Assuming that you’ve installed the software first, you can be up and printing within minutes of opening the box.

The EggBot Pro begins shipping this week. We’ve also put together a little comparison chart, so you can see how it fits in with the rest of the family.

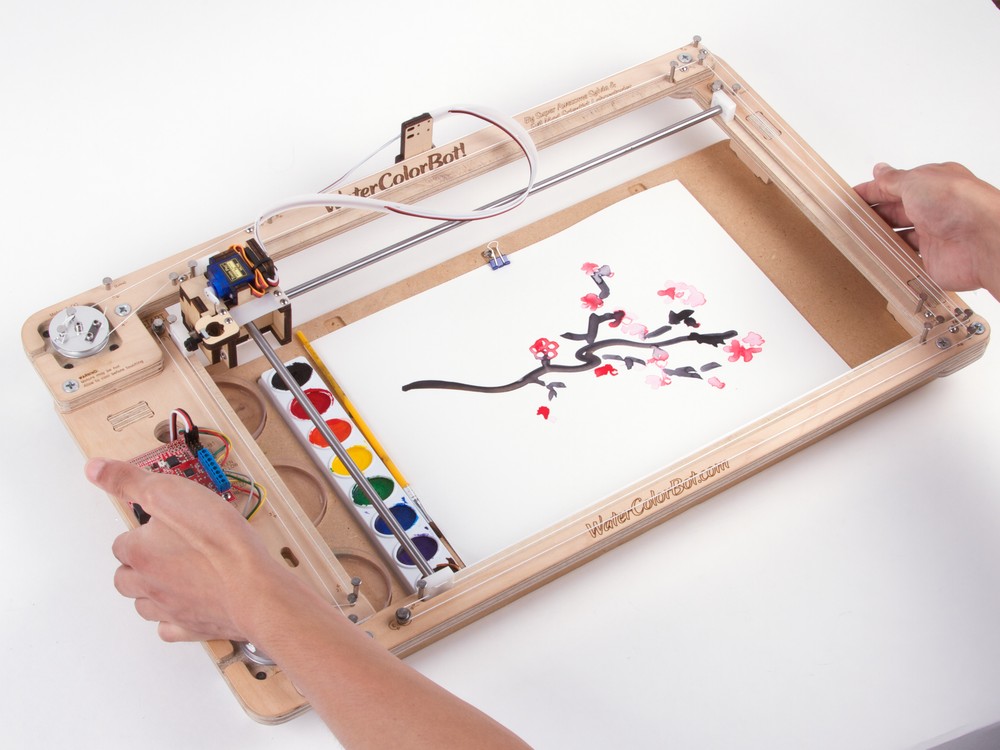

We’ve just given the WaterColorBot a little bump up to kit version 1.5. The new version now comes with a pair of beautifully machined aluminum winches.

The winches are precision cut on CNC machines and anodized clear. We add a few extra little parts (flat-head rivets to wind the winch around, screws, and a stamped and polished stainless steel “clamp” to hold the string end), and wind them with the same “100 pound” Spectra cord as we did before.

We described the process of making and winding our older laser-cut wooden winches in our blog post about the making of the WaterColorBot, and again in our post about the winch cutting jig. For better or worse, transitioning to the new aluminum means that we’re no longer using our older wooden winches that we described in those blog posts. But in the end, these new winches are a better, more elegant solution.

WaterColorBot kit version 1.5 is now shipping from the Evil Mad Scientist Shop.

For the robotics team that we mentor (FRC team 3501), we created an “Advanced Bristlebot Competition” to serve as an off-season team building exercise. We are publishing our competition template (PDF download) here so that anyone can use it as a starting point for their own events. The goals of the competition are to provide a self-contained, resource-constrained and time-limited introduction to a robot competition environment, and to get new and continuing students working together on solving simple engineering challenges.

The competition consists of three challenges: sprint (distance time trial), mountain climbing (same, on an inclined plane), and sumo (a two-robot competition that rewards going in circles).

The group of students is split into teams of two, trying to pair new students with team veterans.

Each team is given a set of rules and a small pile of toothbrushes, motors, and batteries.

Beyond this, one table is designated for tools and supplies, and has an assortment of craft supplies including things like coffee stir sticks, wires, twist-ties, googly eyes, pipe cleaners, pom-poms, and tape. Building tools include hot glue guns, scissors, bolt cutters (for cutting the heads off of toothbrushes), and wire strippers.

After a building period, the robots are “bagged and tagged” prior to competition. For the BristleBots, this means they are placed on paper plates marked with their team number for inspection to ensure that they meet the competition requirements.

The competition takes place in two rounds, separated by an interval of building time between them. The extra time allows the students to redesign and implement changes based on what they learned during the first round of matches.

We witnessed a couple of great moments during our event. We overheard some students watching our original BristleBot video on a phone, and when they noticed us watching them, they defended themselves, saying, “The rules don’t say we can’t!”

One of the most technically inclined students on the team, after building several prototypes and studying the performance of his BristleBots on the ramp for about 10 minutes asked, “This can’t actually be done, can it?” Minutes later, a veteran student from another team, proudly set his robot on the ramp and it whizzed up in one solid go in about 10 seconds. Later, during competition, another student watched her BristleBot zoom up the ramp in 3 seconds flat, using a variation on that successful design.

Materials & Resources

Ever since we released our Three Fives discrete 555 timer kit last year, people have been asking us “When are you going to come out with a 741 op-amp?” It has taken us quite a while to get here, but the answer is… Today!

Our XL741 Discrete Operational Amplifier is a real, working op-amp that you can build yourself. It’s a transistor-scale version of the original ?A741 integrated circuit, that incredibly versatile and popular analog workhorse. As with our 555 kit, you can probe inside to see the inner workings of the circuit as it works. And, like our 555, it comes with a beautiful anodized aluminum “IC legs” stand, so it even looks great when it isn’t plugged in.

The kit was designed and developed as a collaboration with Eric Schlaepfer, and is a direct adaptation of the equivalent schematic from the original Fairchild ?A741 datasheet.

If you’ve ever used operational amplifiers, you’re probably familiar with the ?A741 (or colloquially, just “the 741”). Designed by Dave Fullagar and released by Fairchild in 1968, it’s the quintessential and most popular op-amp of all time. While newer op-amp designs easily outperform the ?A741 in just about every possible respect (speed, noise, voltage range, and so on), the 741 remains widely beloved and in active production by multiple manufacturers even today — over 45 years later.

And, if you haven’t used an op-amp, this a great way to learn. Op-amps are simple, wonderful building blocks for making analog computers. With op-amps, you can build circuits that can (for example) add, subtract, amplify, take logarithms, perform integration, or perform other operations on your signals. Or buffer and copy them, or cleanly convert current to or from voltage, and on and on and on.

A regular op-amp is an integrated circuit; a little black box. The XL741, on the other hand, is a big black box, with a heck of a lot of points where you can can probe inside, to see what’s going on, in real time. And that’s a unique opportunity.

The XL741 is a quick, easy to build soldering kit, with through-hole components, and not too many of them. (And, have you see our awesome resistor wallets?)

And, best of all, the XL741 is in stock, and begins shipping today.

Visit our store page for links to the XL741 datasheet, assembly instructions, and additional documentation resources.

Umbrella Upcycle is a project site filled with things you can do with cast-off and broken umbrellas, including our Better Bat Costume. The project is aimed at reducing the numbers of umbrellas that end up in landfills, and they link to project tutorials, methods of recycling, and recommend places to donate both umbrellas and finished umbrella projects.

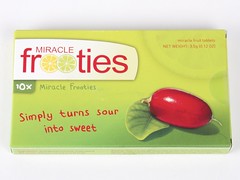

There are culturally common activities like wine and cheese tastings that explore variations of a particular theme. There are also flavor tripping parties specifically for trying out the taste bud altering miracle fruit. And there are molecular gastronomy and modernist cuisine that are intended challenge your expectations of texture and flavor. In the spirit of these kinds of experiences, we came up with a wide-ranging set of interesting (and sometimes challenging) items that can be shipped through the mail and shared between internet friends.

The goals of the project include isolating a few interesting flavors that are not normally tasted on their own, understanding a bit about the ways that shape and texture affect flavor, and play a bit with some of the available “mouth altering” spices and flavors.

Most of the items we included in our tasting kit are from Indian or asian grocery stores. For herbs and spices, getting them from a shop with high turnover will help in obtaining fresher spices that are more full of flavor. They’re also likely to be less expensive at places that expect larger quantities of spices to be used in foods (we’ve written about this before). Ethnic groceries are better at this than mainstream ones, and places with bulk bins can be just about the worst. A few items we shopped for online, and a couple came from our garden.

For tasting order, we opted to start with more subtle flavors and end with mouth-altering ones. Our general itinerary was divided into four parts: flavors & scents, shapes, adventures, and light.

Of special note: many people are sensitive to particular (and sometimes esoteric) food items. Be sure you have discussed food allergies with all participants before plying them with unknown ingredients. Decide if you want to try things before announcing what they are. Have water and neutral flavored crackers or bread for cleansing the palette between flavors as needed or desired.

One of the joys of life is introducing people to new flavors and textures that you love, whether they are from your own kitchen or your favorite restaurant. Every so often, that will backfire, when someone ends up not liking your beloved dish. But sometimes you’ll see that “eureka” moment when someone lights up from the new experience. Eating involves many kinds of sense perception, including smell, taste, texture, temperature, and sight.

An exploration like this is fairly simple to lead when everyone is in the same place, but can also be done remotely. We packaged up our ingredients into little bags and tucked them into plastic organizer boxes (commonly available from the dollar store) to conceal the contents until the right moment.

The list above is strongly influenced by our personal experiences and cooking preferences. Depending on your background, things we find exotic may seem perfectly normal. It is interesting to see which ingredients stir up memories from the participants, and which are new to them as well. If you come up with other ideas, we’d love to hear about them!

Editor’s note April 10, 2021: This article has been edited to remove the word kaffir, which is offensive. Makrut is the preferred name for the fruit, which is also called Thai lime.

We’ve just updated our extensive online documentation for the EggBot with a new visual guide to troubleshooting quality issues.

Pictured above: The natural result if you happen to not tighten the thumbscrew to hold the pen in place: HELLO WOR<ARRRRrrrrrrggggghhhhhhhhh>.